Showing all pages regarding people management.

Why diversity targets won’t help the Big Four

The spotlight appears to be on the big four accountancy firms as they struggle to address the lack of diversity in their partnerships. The domination of white men from elite universities continues in these firms with Ernst and Young, for example, reporting that just 17% of its 549 partners are women. Clearly the people occupying senior positions in these companies ought to more closely reflect the diversity of its client organisations and society as a whole – it makes good business sense quite apart from being seen as a progressive and fair employer. Yet the pressure to address current imbalances at the top suggests that some firms are placing more priority on the achievement of diversity targets than on the quality of their partners or the inherent causes of male-dominated workplaces.

Ernst and Young has announced that, within 3 years, at least a tenth of its new partners will be black or from other ethnic minorities. It has also pledged to make at least 30 per cent of its new partner appointments women in the same time frame. Such ambitions might be impressive but are surely misguided. Where are these senior women and ethnic minority partners going to come from? We know that most women entering management roles in the city tend to leave in their thirties or fail to achieve promotion to senior levels. Maternity breaks and child care responsibilities and are part of the explanation for this but there is also evidence that corporate culture discourages women from aspiring to senior management roles. Being a partner means long hours and the high stress involved makes it difficult for women to cope with the demands of work and family. On top of this, the male-dominated, performance-driven culture is off-putting to many highly capable young women.

Any company that is serious about achieving diversity at the top needs a long term talent management strategy. The aim should be to ensure that the firm’s organisational culture and policies reflect a genuine desire to engage, develop, support and promote talent – wherever it comes from. The desire to achieve diversity at senior levels in business should be welcomed, but the problem cannot be resolved overnight. A slavish and superficial focus on targets alone suggests that the top firms are paying lip service to what is a complex and more deep-seated issue.

The value of an MBA

There was an interesting discussion on Radio 4 this morning about the value of an MBA and whether MBA study was worth the investment. Josh Kaufman, author of ‘The Personal MBA’ argued that successful businesses are built on a few basic principles and that the greatest entrepreneurs learnt by experience, not in the classroom.

These views – that you can’t teach good leadership and that the MBA has little value – have been around for a long time. Business schools do a good job of defending their position by highlighting the scope and rigour of the MBA and its importance in terms of career progression and earning power. Still the debate rolls on.

It is well known that I have my criticisms of the MBA and have long argued for a fundamental review of the qualification (see my article in the FT on 16 April 2012). However, despite its faults I still believe that MBA study is worth the investment (see my presentation to the City of London Business Library http://www.slideshare.net/jeanettepurcell/10-reasons-why-you-should-get-an-mba-14264411).

So while I welcome the ongoing discussion about the MBA’s future and sympathise with some of the critics of the qualification, I take issue with the argument that is has no value. In particular I do not accept the claim that you only learn how to do business by experience.

First most people’s experiences in business are limited to a single industry, sector and job role. Granted, we learn a great deal from experience, but there is no guarantee that our experiences will cover all aspects of business and management. The MBA fills those gaps in our work experience, giving us access to knowledge and skills that we wouldn’t acquire just by being ‘out there’ in business.

Second, learning by experience is only really effective if we reflect on that experience, analyse it and use it to inform our actions and behaviours in the future. MBA study provides the environment, specialist support and structure for such reflection – encouraging students to share and discuss their experiences so that experience becomes the basis for further learning and improvement.

Let’s have an honest debate about the MBA and its future. But let’s not pretend that experience is all you need in business. It’s the depth of experience and what you do with it that counts.

Why 360 degree feedback works

One of the most valuable attributes a leader or anyone in a management role can have is self awareness. With a deep and accurate understanding of yourself; your strengths, weaknesses, habits and preferences, you have the basis for becoming a great leader. Not only can you make the most of your strengths and address your failings, but you can also build a team around you that fills the gaps in your own skill set. For instance, I am aware of my tendency to get excited about new projects and my desire to get going as soon as the idea finds general support. I tend to overlook the detail at this stage and can overlook potential risks. As a Chief Executive I made sure that my top team included someone I trusted to always consider the detail and to keep my enthusiasm in check if necessary.

But self knowledge can be difficult to acquire – we are often blind to our own personality traits and don’t see what others see in us only too clearly. That’s why it is important to get feedback from people you work with in a carefully managed and anonymous way. I use 360 degree feedback quite regularly with senior managers and teams and I have seen how the results can change behaviour and improve performance. The feedback gives you better self knowledge and shows you how you are perceived by others. Such rich information not only forms a great basis for self development but also provides a tool for measuring improvement (by repeating the same feedback exercise in, say, 6-12 months time).

360 degree feedback involves the identification of a group of people who you work with whose opinions you value and trust. Normally the number of people chosen will be between 6-12. The selected group should include a good cross section of work contacts (for instance a mix of peers, managers, juniors, external clients, board members etc). Ideally you should avoid choosing only the people you like or who you know like you, but you should be confident that the feedback you receive will be constructive and helpful.

The feedback questionnaire can be designed to give general feedback on a number of management issues. Alternatively it can be specific, focused on giving some in depth feedback on an issue where the aim is to build new skills (e.g. effective communication). An independent expert should develop the questionnaire ensuring the questions are valid, clear and fair. All questionnaires are completed anonymously and returned for analysis by the independent expert who then presents the results to the people concerned in a professional and constructive way. Of course, the results might be surprising or even upsetting and so this stage must be handled sensitively. However, it is often the case that people recognise the need for improvement when presented with the evidence. They are also pleasantly surprised at positive feedback which they hadn’t expected.

There are a range of costly and sophisticated business tools used to help improve self knowledge and our understanding of the people we work with. I prefer 360 degree feedback above all of these. It’s simple, relevant and cost effective. Most importantly, it works.

How to get a return on your (training) investment

A recent article by Robert Terry in the Financial Times (FT) complains that, despite the significant sums spent annually on training and development by companies, very little of what is learnt translates into improved performance in the workplace. Studies shows that only 5-20% of the learning from training has any impact on the business. Given the current obsession with measuring everything against business targets, this is puzzling if not shocking. “Surely” Terry suggests “a training industry that delivers less than 20 per cent cannot be fit for purpose.”

He is right. Much of the training delivered globally, within companies or by universities, is probably ineffectual. Yet still many organisations fail to measure the impact of training on the business and individual performance. Terry suggests that one reason for this is the lack of any participation or involvement of line managers in individual staff development. He argues that managers fail to take responsibility for the learning and development of their staff and should be held to account for the transfer of training to the workplace. Trainers should also be more concerned with the application of training and how it will benefit the business.

As a leadership development specialist I take this issue very seriously and have long been promoting various approaches which help to ensure that companies and individuals get a return on their investment in training and development. First let’s look at business schools and the MBA – generally considered to be the leading international business qualification. I am a strong advocate of the MBA, but, despite the considerable cost of tuition, there is surprisingly little evaluation of how the qualification benefits business or its impact on individual performance. Many employers express the concern that MBA training is too divorced from the reality of business. Some are also reluctant to sponsor employees to take an MBA because of the risk that, once qualified, their employee will be off to find a higher paid job with better prospects. Many companies attempt to manage this risk by ‘tying in’ the employee with a contract requiring them to stay with the company for a certain period after qualifying. Well, it may stop them leaving but does this restraining order really help employers to get the most out of their highly qualified senior staff?

To be sure of a better payback, employers need to take a more considered approach to MBA sponsorship. I have always encouraged employers to address the following questions. Which employees would you select to support through their MBA training and why? How can the business get the best return from investing in MBA training? What are your long term plans for the development and progression of your most talented employees? While these employees are training, or when they are qualified, what new opportunities and challenges are you able to offer them? How will their new learning be applied in order to benefit the business? Dealing with these questions will not only keep senior staff motivated and engaged but will also help to ensure that employers realise the full value of MBA training.

Then there is workplace or corporate training. How do we improve the transfer of learning in this context? It’s true that some managers are too ready to shirk their responsibility for staff development, turning to HR to solve their performance problems with the wave of a wand or the provision of a 2 day training course. When I am asked to provide management and leadership training I spend some time during the planning stage with the CEO, line managers or ideally the management team. The aim is to get an understanding of the business, the people, the challenges they face and any specific performance problems so that I can make what I deliver as relevant and meaningful as possible. I want them to see my participation as an intervention in their company’s business process, picking up on what is already going on and developing ideas and actions for implementation in the future. It is essential to get the manager’s or CEO’s commitment to deal with any follow up and to support further development after my input. That way the training and development doesn’t end when I walk away.

Measuring the impact of training on business performance isn’t easy. But with a considered approach to staff development, the involvement of managers and input from trainers who are concerned with the application of learning, the returns can be considerable.

The Imposter Syndrome

I heard the term ‘imposter syndrome’ for the first time today. It described a situation I recognised immediately and have often talked and written about – and I was fascinated to hear that the situation has a formal definition. The term popped up during an interview with one of the world’s leading astronomers – Dame Jocelyn Bell-Burnell – on Radio 4 this morning. She described how she pursued a career in astrophysics in the 1960s, struggling to achieve recognition in an entirely male dominated field. She applied for a PhD post at Cambridge University not expecting to get in and, when her application was accepted, she was very surprised. Jocelyn Bell-Burnell remembers her first year at Cambridge as a very daunting experience. She felt she didn’t deserve to be there and, in her interview, talks about ‘imposter syndrome’ as a way of describing her feelings. To paraphrase Jocelyn’s explanation of the syndrome : it is experienced by people, mostly women, who lack confidence and who believe that the success they have achieved is the result of some terrible mistake. The feeling involves a nagging fear that at some point the mistake will be uncovered, revealing the person as an undeserving imposter.

This feeling will resonate with many women and, perhaps, some men. To some extent I experienced it myself when I was first promoted to a senior management position. Despite the rigorous selection process, I couldn’t help wondering whether I got there by luck or by somehow pretending to my seniors that I had got what it takes. My older sister, a successful occupational therapist and academic, has told me that she occasionally felt like a fraud in her job. She half expected someone to tap her on the back one day and say “sorry, we’ve just realised you’re not up to this job and you’ve been getting away with it for too long”. When I am coaching women in senior roles it is not unusual for them to express feelings of doubt about their ability to do their job. They are also quick to tell me why they are probably not capable of progressing any further. I rarely encounter a man expressing the same reservations.

Women who suffer from this lack of confidence are often their own worst enemies. They fail to aim high, underrate their own capabilities and do themselves down in front of others. I am not suggesting that women should learn how to be more arrogant – it is often the sincerity and honesty of women leaders that earns them respect, trust and success at the top. Rather I wish that women would believe more in themselves, acknowledge their strengths and realise the positive impact they have in business. I can well understand Jocelyn Bell-Burnell suffering from ‘imposter syndrome’ in the scientific field in the 1960s. It shouldn’t still be happening today.

It’s Good to Talk

Recently I completed a project for a highly respected financial company, renowned for its innovative approaches to staff development, engagement and communication. The company had made a significant investment in a new project which involved some risk and uncertainty but was nevertheless considered essential for the company’s survival in a competitive market. When I became involved the project was faltering. Unease was growing about the likelihood of achieving success or, at least, of making any return on the investment to date. On the surface there were a number of explanations for the anxieties. Staff changes in key areas had led to some lack of continuity, feedback from some of the first trials had not been entirely positive, and there was a realisation that more investment would be required to achieve the original vision. With no prospect of income from the project in the short term, there was a fear that the company had bitten off more than it could chew.

My task was to get the project back on track with a plan for the short and long term and recommendations for addressing the financial concerns. This is the sort of challenge I love! It involves elements of change management, strategic review, market analysis and financial planning and all of those issues came into play here. However, looking back on my experience as a consultant for this company, I am convinced that the most important success factor in this project was in fact communication. As I began to understand the context and to unearth some of the underlying issues affecting the project’s progress, it became clear to me that the expertise, the ideas, the information required to get things moving were right there in the company. But communication had broken down, information was not being shared, grievances were being allowed to fester and confidence was fading. I am not blaming the company for this – even the best organisations find that, in some situations, established practices for ensuring good communication just don’t work. In these circumstances it sometimes helps to bring in an ‘outsider’ to find out what’s going on, get people round the table and encourage them to start talking again. In this project I didn’t need to provide all the answers, the people I spoke to had a good idea of what had to be done. All I did was to listen to views and ideas, co-ordinate the required actions and provide a structure and a plan for the way forward. The result was a more energised, optimistic team with a clear understanding of what was going to happen over the next 2-3 years. The vision was once again achievable.

Good communication is undeniably important in business. It sounds so elementary, I wonder why so many organisation still fail to get it right. If my experience with a company that knows how to do things well is anything to go by, I fear for the others.

A shocking waste of talent

More on the subject of women in senior management. The UK’s Institute of Leadership & Management (ILM) says that, according to its research published last week, there is a strong link between low confidence levels in women and their lack of career ambition compared to men. The Institute’s survey found that the career ambitions of women lagged behind their male colleagues and that over half of the women managers interviewed reported feelings of self doubt at work, compared with just 30% of men. Let’s consider this against the ongoing debate about female representation on Boards (and calls for quotas to address this) and another recent report by the London School of Economics (LSE). The LSE research identified a strong trend towards entrepreneurialism amongst women , reporting that 70% of women aged between 16 and 24 have ambitions to set up their own business.

These findings reflect my own experience both as someone who built a career in management to become a Chief Executive, and as a specialist in the global MBA market. Confidence amongst women at work is an issue. Women MBA graduates who are asked how they benefited from the qualification will invariably say that the experience gave them greater confidence in their abilities and more self esteem. I am also struck by the number of women who attribute their career success to the support they received from a great boss or someone in their past who gave them confidence and pushed them to go further. At the same time, annual surveys into the career choices of MBA graduates show an interesting increase in the number of women MBAs who are choosing self employment as a career. It might be possible to conclude from all this that women, lacking the confidence to compete with men in the corporate world, are opting out by establishing their own businesses and succeeding on their own terms. This is an over simplification – running your own business is not an easy option: it involves high risk, requires confidence, an appetite for success and a competitive nature. But given the consistently low numbers of female senior managers employed by companies and the under representation of females on Boards, it is not hard to understand why self employment is an attractive career path for many women.

This situation presents a serious problem for companies who are struggling to find talented people to fill top positions. We know that, with the retirement of baby boomers and a declining birth rate, the talent pool is shrinking. If female employees with potential to progress are not encouraged in their careers, or if women are simply leaving to go it alone, companies are losing an internal resource of skills, knowledge and expertise. A proactive talent management strategy which seeks to spot potential, nurture and encourage staff with promise, and which removes obstacles that might be preventing the advancement of women employees would go a long way to addressing these issues. It makes good business sense. Recruiting new staff from outside is costly, time consuming and risky. Investing in identifying and growing your own talent is likely to be a far more effective and efficient option.

Follow the Leader

A recent two part BBC Radio programme (“Follow the Leader” presented by Carolyn Quinn) did a good job of exploring the concept of Leadership and some of the current issues facing Business Leaders. I was surprised though, that there was very little emphasis in the programme on the question of ethics or moral responsibility in business, particularly in the wake of corporate scandals, the banking crisis and environmental disasters such as the BP oil spill. These recent events have heightened the debate about the integrity of business leaders and have led to some interesting discussions about the subject of morality in business. I prefer the term ‘responsible management’ which goes beyond the rather tired notions of ‘corporate social responsibility’ and ‘business ethics’ and represents a deeper and more meaningful approach to the issue.

“Follow the Leader” began with various politicians and business people attempting to define leadership and what it is that makes a good leader. Rightly, the need for a clear vision and sense of direction was stressed. There was also general agreement that leaders need to be decisive, confident, strong, thick-skinned and with a competitive attitude. I wouldn’t argue with the value of these qualities in certain circumstances but it was disappointing that no one thought to mention the importance of honesty, integrity or conscientiousness in the context of leadership. How can a leader without these qualities hope to command genuine respect, or to inspire and motivate others? The programme’s second episode opened with a discussion about the greater visibility of leaders today. The rise of social media and aggressive press activity means that those with influence and power are much more exposed and that news of any gaffs or misdemeanours will travel fast, worldwide. Contributors to the programme suggested that, as a result of this increased scrutiny, leaders needed to be more mindful of their actions, pay attention to image and manage the risks to their reputation. Well, although this is good advice, it is again disappointing that the emphasis is on ‘keeping your nose clean’ rather than leading according to moral principles, personal values or an inherent sense of responsibility. Leaders are, first and foremost, human beings, with flaws and weaknesses as well as strengths. A genuinely effective leader puts effort into understanding themselves and others. Their leadership style and approach to business is informed by that understanding and is determined by their own moral code and set of values. These values are strongly communicated, drive the business and form the basis for all decision-making. Ask most people to think about a leader they admire or who has inspired them and I can guarantee that, although ‘strong’ and ‘thick-skinned’ might be amongst the admired qualities, ‘integrity’, ‘honesty’ and ‘concern for others’ are more likely to be at the top of the list.

Can leadership really be taught?

There appears to be an increase in cynicism about business education and qualifications, or those who argue that ‘real life’ work experience is of more value than management training. The myth that leaders are born not made is often perpetuated by ‘self-made’ business leaders who have achieved success without any formal qualifications and who claim to have worked their way to the top by sheer determination and an entrepreneurial spirit. These qualities, the cynics argue, are inherent – ‘you can’t teach leadership’.

” business education can’t change personalities, but it can help individuals to think and behave differently”

Well there is no denying that experience counts for a lot and that certain behavioural traits, such as confidence, intuition, creativity, and a positive attitude can all contribute to effective leadership. However, I would argue that, while business education can’t change personalities, it can help individuals to think and behave differently in management and leadership roles. But then the cynics go on to argue that it is not possible for the classroom to replicate the complexity of today’s global business environment. Business schools can teach the theory, they say, but formal education can’t prepare students for the reality of business which involves uncertainty, managing change, working across cultures, and managing people.

“the exercise taught the students something about collaboration, leadership, and what makes an effective team”

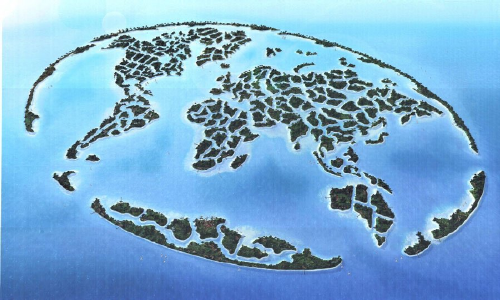

Having worked in business education for many years I take issue with the implication that business education is all theory and no practice. The best business schools in the world are offering high quality programmes which combine the teaching of theory with innovative approaches to developing skills and experience in a practical environment. Two weeks ago I was working with a group of seven new MBA students on a workshop designed to develop leadership skills, focusing particularly on team working. One exercise, which was filmed and played back to the group afterwards, involved a task where the group had to create products from materials according to a given specification, within budget and within a specified time frame. By the end of the exercise, the group having completed the task, watched the playback and discussed what happened, I had witnessed a noticeable change in the attitudes, behaviours and skills of the group members. Of course the changes were small, and I am not saying that one workshop can transform individuals into leaders. But there is no doubt that the exercise taught the students something about collaboration, leadership, and what makes an effective team. Not only that, each member of the group came from a different country (as is usual for MBA students). The nationalities represented were Greece, China, India, Iran, Russia, UK and the US. For the first time, these students experienced what it was like to work with people who spoke different languages, came from diverse cultural backgrounds, held different values and were used to different ways of working. The learning from this cross cultural team trying to work together to get a job done was extremely powerful.

So don’t tell me that education and qualifications have no value or that business courses can’t prepare students for the reality of business. Good programmes, involving a mix of teaching, coaching and practical assignments are arguably the best preparation for leadership. Business education alone can’t replace the benefits of real work experience, but it can enhance and complement that experience which, after all, is always going to be limited.

Dubai Student’s Dilemma

While working with a group of MBA students in Dubai this month one of the students, Mohammed, a 35 year old engineer from Bahrain, asked me for help with a problem he was facing at work. He had applied for promotion to a position which involved line management responsibilities. Mohammed’s company was apparently apprehensive about appointing him to this new role, not because he didn’t meet the requirements of the job, but because they didn’t want to lose him from his current position – he was working in a highly technical, high risk area of the business and there was no one else in the company who could do that job. Mohammed wanted some advice on how he could persuade his employers to release him from his current role. His approach to me triggered a number of thoughts. First, I sympathised with the sense of frustration Mohammed felt at effectively being too good at his job and too valuable in his current role to achieve promotion. How many employees with potential and ambition are simply not encouraged to put themselves forward for promotion because, to do so, would leave their employer with a recruitment problem? This tends to happen in areas where specialist, technical skills are scarce or where the wealth of knowledge and experience that one person has accumulated in a role is difficult to pass on and no thought has been given to succession or contingency planning. The implications here are clear. Companies that fail to ensure that skills and knowledge in an organisation are shared and communicated (even documented if necessary) are putting the organisation at risk. In addition, those companies that fail to encourage talented staff to develop and to take on new challenges are likely to lose their good people or, at the very least, their motivation and commitment to the company.

But I was also struck by Mohammed’s question to me for another reason. Here was a mature, experienced male with an engineering background who recognised that he needed some help and advice to overcome the problem he faced. He was being honest with me that he didn’t know what to do. Far too often I am dismayed at how unwilling some people are to ask for help and how many opportunities to get great advice and new ideas are passed up. The reasons are not clear – could it be because of pride or is it arrogance?. I have always found that, when facing a difficult business issue, there is normally someone around who is willing to help, give advice or offer a new perspective. Just ask! As for my advice to Mohammed – perhaps I’ll make that that the subject of a future blog!